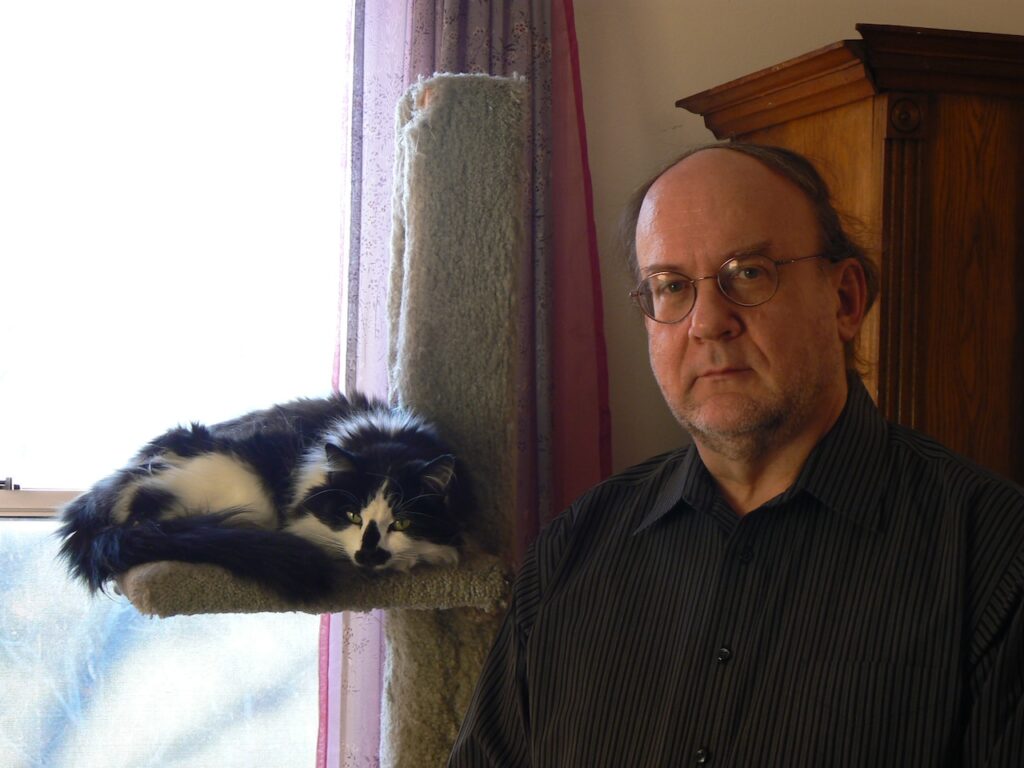

Nick Leiber

John Boston is one of America’s leading prisoners’ rights litigators and co-author of the bestselling Prisoners’ Self-Help Litigation Manual, which has aided countless incarcerated individuals and attorneys navigating the U.S. civil litigation system. As the former director of the Prisoners’ Rights Project of the Legal Aid Society of New York City, Boston helped bring landmark cases against officials who violated the rights of incarcerated people in New York State’s jails and prisons. Boston’s other book, PLRA Handbook: Law and Practice Under the Prison Litigation Reform Act, helps incarcerated litigants avoid pitfalls imposed by the federal statute. He is working on a fifth edition of the Prisoners’ Self-Help Litigation Manual with co-author Dan Manville. Boston, who joined Legal Aid in 1976, retired in 2016, and continues as a volunteer, spoke with CUNY Law Review Digital Editor Nick Leiber about his life’s work, strategies for obtaining justice for incarcerated individuals, and what brings him hope. This interview has been edited and condensed for length and clarity.

NL: Was there an experience before law school that made you want to get involved in this work or did that happen in law school?

JB: A little of both. I went to college in the late 1960s and graduated in 1970. I worked for a couple of years and had to decide what I was going to do. I kept reading in the newspapers about promising things that were happening mostly in the federal courts—judges striking down arbitrary rules and abusive practices in prisons. Law seemed to me like the way to do something politically useful that was more congenial to my somewhat academic temperament than politics itself.

NL: So you went to law school?

JB: Practicing law—practicing civil rights law and poverty law—seemed to be a possibility for me. And of course one of the more abusive institutions in American life has long been the criminal justice system. I got involved in some litigation about the criminal justice system while I was in law school. And it was interesting and worthwhile, even though we lost at every stage.

NL: And after law school?

JB: When the opportunity to apply to the job at the Prisoners’ Rights Project came up, it was right in the center of what my interests were, although I could have gone into litigation concerning other kinds of institutions—welfare, school systems, etc. But the opportunity was inviting and when I got there, it turned out to be what I wanted to do. So I then did it for essentially the rest of my career.

NL: How did you get involved with the book?

JB: James Potts, a formerly incarcerated man working at the American Civil Liberties Union’s National Prison Project (NPP), and Alvin Bronstein, NPP’s director, were the authors of the first edition. It was published in 1976. Dan Manville, who himself had served time in prison and then gone to law school, got involved with trying to get out a second edition while interning at the NPP. One of the people there suggested he call me. This was exactly the kind of thing I was helpful with because I had made a compendium of organized case law.

The second edition of the book, which was the first one I was involved in, came out in the mid-1980s. Dan Manville was listed as the author. I was listed as the editor. We continued. The third edition came out in 1995. We released a fourth edition in 2010. We are currently working on the fifth edition. The manual is the single most valuable thing I’ve been involved in. More so than any single piece of litigation. Although if you compare the totality of all the litigation I’ve been involved in, you might get a different answer.

NL: What is the book’s goal?

JB: There are two things going on. The overt mission is to tell prisoners how to litigate for their civil rights in a way that is understandable to them; and the other was to make it complete enough that it’s useful to lawyers doing prisoners’ rights work.

NL: Why did the book resonate?

JB: It’s a tool for people who want to try both to make their immediate situation a little bit better and to cultivate different ways of thinking about that situation. It puts your day-to-day life in prison into the context of a legal structure that has its roots outside of the prison. It gives you a very sharp appreciation of the extent to which the legal system has institutionalized a great deal of abusive treatment simply by setting standards that don’t say it’s fine to abuse people, but do set the bar for showing unconstitutional abuse at such a high level, that even if you prove your case, you lose.

NL: Can you offer a sense of who is using the book?

JB: It’s widely distributed and widely known. At one point, I was having an exchange with someone at the publisher about the importance of getting moving on the fifth edition. They said, “we sell more copies of your book to prisoners than we do the Bible.” Of course, there are plenty of other places where people can get the Bible, so it’s not quite a fair comparison.

I went to a conference probably in 2010 or 2011. It was at a law school, but it was open to the public. At the end of whatever presentation I was on, this guy walked up. He had a big three-ring binder. He said, “I wanted to meet you and thank you. This is my Self-Help Litigation Manual that I had with me through the years I was in prison.” It was now falling apart. The pages were all punched through for the binder and incredibly dog-eared. This was something that had seen a huge amount of use. He asked me to autograph it for him, which I did with great pleasure. I don’t get that kind of feedback very often, but I know it’s widely used, and widely appreciated among prisoners.

NL: What does it take to reform a prison or jail that regularly harms incarcerated individuals? Asked another way, what is a good example of how to put together a compelling pattern and practice case?

JB: Fisher v. Koehler, which was decided in federal district court in 1988 and affirmed on appeal, illustrated better than anything else we’d done in writing, how you have to construct institutional litigation. The case concerned violence in New York City’s misdemeanor jail on Rikers Island—both violence by staff against prisoners and violence between prisoners, which was out of control for what was essentially a low-security population—I mean, these were misdemeanants and people serving very short sentences. It’s a case that went to trial and the judge wrote a very long and detailed opinion that allows you to see how it was put together. You don’t always get that, even when cases go to trial. And most of these cases don’t go to trial. Most of them are eventually settled.

NL: What are the mechanics of these kinds of institutional reform cases?

JB: Most have to be built layer by layer. You read that Fisher decision and you see, first, on the bottom level, that people came into court and testified as to bad things that happened to them. Second, you see a lot of paper evidence from the prison’s own records showing that these were not isolated incidents; that there was a great deal of this kind of conduct. Many, many people were involved in violent incidents and suffered significant injuries. And many of the incidents involved the same assailants; both staff and prisoners over a period of time and nothing was being done to curb the conduct of those individuals. You can glean this by poring over the records, which I did for many, many months.

Then, on top of the paper discovery, there is the testimony of experts about, first, what the evidence meant to them in terms of the gross number and severity of the incidents that were happening and, second, the reasons that it seemed to be happening based not just on reading the records that my colleagues and I had pored over but also visiting the facility, reading depositions, talking to some of the staff and the administration in the jail.

On top of all of that, the next layer is fitting all the facts into a legal framework and trying to come up with proposed remedies that were responsive, not just to the severity of what was happening, but also to the reasons that it was being allowed to happen. In other words, what are you going to do about this?

The litigation process in these kinds of cases also involves educating the defendants. By that I mean educating the defendants’ lawyers, who if they’ve been listening to their clients, don’t necessarily have much of an understanding of what’s going on. And, very often, their clients don’t have an understanding of what’s going on, at least at the level that we did from making a concentrated study of the operations of the institution. The defendants’ bureaucratic institutions are not necessarily reflective. They have ways of doing things. There are interests that have to be negotiated within the institution between the people in charge and the people who do the work on a daily basis and that creates a culture that has inertia.

NL: Beyond translating the law into books that are helpful to incarcerated people, how do you see your role as an attorney?

JB: I like to say I work as a “human rights mechanic” because the job is not just to expose terrible things that are happening and yell about them but to come up with ways of doing something about them—often ways that the people in charge of the institutions are reluctant to implement. Otherwise, they would have implemented them already and we wouldn’t be having this conversation in court with witnesses, experts, documents, and so forth.

NL: How did your work change after the Prison Litigation Reform Act (PLRA) was enacted in 1996? The statute has been described as “slamming the courthouse door” on incarcerated people.

JB: The 2003 Second Circuit decision Benjamin v. Fraser gives an idea of what the playing field is like for prisoner litigation after the PLRA. The case was not affirmative litigation. It was the other end of the process. We were defending consent judgments that we had obtained in the 1970s and some additional later orders against efforts by New York City to terminate them on authority of the Prison Litigation Reform Act, which says if there is no continuing and ongoing violation of federal law, defendants can move to have judgments terminated.

The big story here is that while we lost a lot of our ability to correct certain kinds of things and latitude in proposing remedies, we are not out of business yet. The reason for that is no matter how low the constitutional floor is set or how weakened the means of correcting violations are, prison officials still manage to go below it. It’s still a growth industry, unfortunately.

NL: What’s it like to work on these prison reform cases?

JB: We didn’t take cases so much as we built cases. We had good contact with the client populations. It was enhanced by the fact that we were within Legal Aid, which had a criminal defense practice, so they could tell us things that were going on or things they were hearing from the clients. We would try to come to an understanding of what the needs are and what kinds of things presented possible fuel for litigation. And then how to do it. How to frame the case. Where to file it. What its scope should be.

That is what I spent almost all of my entire working life doing. I was very happy that I did. But I had a much more academic, intellectualized approach to things. I do things much less from the gut. I’m much less engaged with humanity on a moment-to-moment basis than a lot of people. The job that I had is not one that everybody would like.

NL: As part of a parole project, I’ve been speaking to an incarcerated man who has been in New York’s prison system for 25 years. He describes a flood of young people entering who lack hope and aren’t interested in participating in educational programs to get high school and college degrees. At the same time, he’s seeing many young correction officers entering who sometimes behave pretty sadistically. Does his perspective track with what you’re hearing?

JB: His observations about the change in the prison population over the years are exactly congruent with my own observations from talking to prisoners over many, many years. When I first started out in the late 1970s, there were a lot more people who didn’t really feel they belonged in prison—it was an unfortunate detour in their lives but they were going to get through it. Meanwhile, they maintained their interests in things that were going on outside the walls of the prison.

Over the years, the number of people who seem to think that way has diminished to old-timers. My observation about the younger prisoners is that they seemed more fixated on prison life with the sort of implicit understanding that there was a good chance that that was going to be their life.

NL: A 2017 opinion piece in the Los Angeles Times suggested that to improve the criminal legal system, all of us should spend three to 90 days in a maximum-security facility every decade—what do you think of this idea?

JB: If we’re building a utopia, it’s worthy of serious consideration. I think that if people actually understood the system rather than just bloviating without understanding, society would operate a lot better.

Another variation on that idea that I heard long ago is that no one should become a judge who hasn’t been a criminal. It’s a slightly more radical proposition, but I think there’s some merit to its radicalness. It might be more difficult to operationalize than the one you’ve suggested.

NL: In terms of how society treats incarcerated individuals today, what, if anything, gives you hope?

JB: One of the things that we’ve been seeing now for a number of years is in cases of death or other serious mistreatment of prisoners—disabling brutality, lack of medical care—there have been some massive jury verdicts. I mean, seven figures, eight figures coming out of places like Oklahoma. The idea that you can’t bring these cases in really red states because they all hate prisoners is changing.

A weaker version of the thought experiment you just mentioned is when you take some people out of their ordinary civilian life and you make them sit there and hear the evidence of what it’s like that led to somebody dying gasping for breath in their cell, or led somebody to go into prison on their feet and come out quadriplegic, or paraplegic, or blind, or deaf, or some other disability because of the way they were treated or neglected. If they have to approach it in that up-close-and-detailed way, and not just in the world of bloviation, you can get to a focus on human beings; you can get past the layers of prejudice.

NL: Any other thoughts for people who want to do the kind of work you do?

JB: Don’t forget state courts. Don’t forget state legislatures and administrative agencies. When I started this work, in about everywhere but California, people had written off state courts as being helpful to people doing litigation on behalf of prisoners and for prison litigation generally—except for matters where there was no federal law claim.

But over the years, attorneys doing this work have become more comfortable with the idea that it is possible to get state courts and administrative agencies with some sort of jurisdiction to make rules and decisions that are helpful.

I think there could potentially be a lot of niches in the system of government below the federal level. Where if you learn the territory, even if you’re not practicing law—say you are in an agency or on legislative staff—you might see an opportunity to make a difference by getting agencies and others to make decisions that are helpful with much less effort than it takes to get a statute out of Congress or a decision out of the Supreme Court.

NL: What advice might you offer someone who is contemplating law school in the hopes of fixing broken legal systems (or at least helping to improve one of them)?

JB: If I were giving career advice to somebody nowadays, I would probably say, think seriously about politics—at least as seriously about politics as you do about practicing law, because that’s going to be the only thing that saves us from authoritarianism. In the past, people had relative faith that the courts would do that. And who, with any sense, really believes that now? That doesn’t mean I would have necessarily made a different decision myself. I would not have been very good at, or very happy, at doing direct political work. But for those who are a little less ivory tower-ish than I am as a matter of personality, give more thought than I did to the political fray.

Nick Leiber, CUNY Law Class of 2024, is the digital editor of the CUNY Law Review.