Recommended Citation: Osha Oneeka Daya Brown, Lee Doane, Sterling Fleming, Hakim Trent, Jeremy Valerio, &and Outside Organizers with No New Jails NYC, $11 Billion for What?! Incarcerated Organizers with No New Jails NYC Explain How to Shut Down Rikers

Click here to view a pdf version of this article

Osha Oneeka Daya Brown, Lee Doane, Sterling Fleming, Hakim Trent, Jeremy Valerio, and Outside Organizers with No New Jails NYC†

The Social Studies class didn’t teach me shits your Honor

We was shooting dice at third period

WE WAS in the bathrooms getting nice smoking

blunts at third period

My principal was a drug dealer

My teachers was drug feelers

My projects was an institution that prep me for

THE Metal fence institution

We went to jail to have family reunions

This is deeper then confusion

No computers, No cellphones

The history class didn’t teach me the truth about

myself I’m actually more valuable than what you

considered to be wealth

The system treated me like a gun used me and placed

back on the shelf the science class didn’t teach

me about health

I’m dominant

We need COOPERATIVE ECONOMICS to reach our

Accomplishments

– Hakim Trent-El

Introduction: No New Jails NYC: If They Build It, They Will Fill It

Formed in the fall of 2018, No New Jails NYC (“NNJ”) is a multiracial and intergenerational coalition of organizers, residents, community members, and currently incarcerated people fighting to close Rikers Island without building any new jails in New York City (“NYC”). Bringing together organizers from the Campaign to Shut Down Rikers,1 Critical Resistance,2 Million Hoodies,3 Black Lives Matter,4 Community in Unity,5 Safety Beyond Policing,6 Take Back the Bronx,7 the Black Youth Project,8 the Audre Lorde Project,9 the Sylvia Rivera Law Project,10 the Incarcerated Workers Organizing Committee (“IWOC”),11 Black & Pink,12 and other movements in the police and prison abolition movement, NNJ was established in the wake of Mayor Bill de Blasio announcing an $11 billion plan to build new jails in 2018. On October 17, 2019, City Council voted to approve that plan13 to build four new jails in four NYC boroughs14 and add three to six jail hospitals to existing public hospitals in Manhattan, Brooklyn, Queens, and the Bronx.15 NNJ is an all-volunteer, grassroots effort that has built its campaign through community and street outreach, abolitionist teach-ins, and mobilization of the leadership, analyses, and visions of people who are currently incarcerated across New York and the country.

The Mayor has sold this as a plan to close the Rikers Island jail complex, which is commonly known as Rikers; yet, there is no legally-binding commitment or mechanism for shutting down the notoriously brutal and violent jail.16Although City Council voted to initiate a land use proceeding to potentially ban the NYC Department of Correction (“DOC”) from operating jails on Rikers after 2026, this “city map amendment” will not be passed until 2021, does not address jurisdictional concerns, and may rely on litigation to eventually close Rikers.17 Moreover, any future Mayor or City Council could withdraw this application or reverse the amendment; this is far from the “ironclad guarantee” that the plan’s boosters have claimed.18

The Mayor, the Independent Commission on New York City Criminal Justice and Incarceration Reform (the “Lippman Commission”), and the Office of Criminal Justice Reform have all exceptionalized Rikers as the worst jail in the city,19 perhaps even in the nation, ignoring the decades of reports of abuse in other city jails.20 Despite their feigned concern with safety and conditions, their plan requires moving all incarcerated people from the current borough-based jails onto Rikers.21 NNJ recognizes that this is a historic moment during which the future of incarceration in NYC will be decided: will we build more cages to abuse, segregate, and murder Black and Brown working class New Yorkers for generations to come, or will we commit to true decarceration and a pathway towards abolition?

In Part I of this article, we provide a brief introduction to Rikers and the political circumstances that have made it possible to envision its closure. In this section, we also discuss the city’s jail construction plan and how the Mayor, City Council, Lippman Commission, and Office of Criminal Justice Reform are laundering it as a plan to close Rikers. In Part II, we summarize the brief history of the failures of jail reform projects in NYC, beginning with the construction of Rikers in the 1930s and ending with the opening of the Rose M. Singer Center, the women’s jail on Rikers Island. Because many of our incarcerated members are trans or gender nonconforming (“TGNC”) people22 caged in men’s prisons, in Part III we discuss the specific harms of incarceration on TGNC people of color, who are hyper-policed, incarcerated at astronomic levels, and face violence, brutality, and denial of their gender identity and gender-self-determination wherever they are caged. Finally, in Part IV, we briefly introduce the cornerstone of our campaign: Divest from Incarceration to Invest in Communities. Here, we share the analyses and expertise of five of our currently incarcerated members, who tell us how they would spend $11 billion to shut down Rikers without building new jails.

I. Understanding Rikers Island

From its peak of caging 20,000 people per day in the early 1990s,23 Rikers currently cages approximately 7,000 people per day.24 Of that population, approximately ninety percent are Black or Latinx people and well over fifty percent have been diagnosed with a mental health or substance use issue.25 Although NNJ does not have the following statistics specifically for Rikers, nationally, jails and prisons lock up poor people and people coerced, policed, and banished through the school-to-prison pipeline. Eighty percent of people incarcerated in New York State are indigent, thus qualifying for public defense,26 and nationally, seventy-five percent of people incarcerated in state prisons have not completed high school prior to their incarceration.27 Jails and prisons lock up poor people, people of color, people with disabilities or mental health struggles, and TGNC people at disproportionate rates. In NYC jails, unlike other large urban jails in places like Los Angeles and Chicago,28 the near totality of incarcerated people are awaiting trial: almost eighty percent of NYC’s jail population is detained pretrial,29 in effect subjected to punishment30 (and death) before ever being found guilty.31 Spending even a single night in jail can cause people to lose their apartments, jobs, and children, can expose them to violence and degradation at the hands of the carceral system, and can exacerbate mental and physical illness,32 initiating a cycle of incarceration.33

Although Rikers has long been a toxic and dangerous place, when Kalief Browder died by suicide in 2015 after having been detained pretrial on Rikers for three years, accused of stealing a backpack,34 public and political attention began to refocus on conditions in city jails.35 Organizers who had been active in police brutality, police abolition, and Black Lives Matter movements in NYC came together with Akeem Browder to form the Campaign to Shut Down Rikers.36 As the campaign gathered steam throughout 2016, Mayor de Blasio claimed that closing Rikers was “unrealistic,”37 even as then-City Council Speaker Melissa Mark-Viverito was pulling together the Lippman Commission, which would eventually release a report in favor of closing Rikers and building five new jails in NYC.38

The Lippman Commission describes Rikers Island as a “penal colony model that needlessly confines thousands of local residents on an isolated Island where they, and their guards, are exposed to inhumane treatment that leaves a lifetime of damage.”39 Yet, the Lippman Commission and Mayor’s plan for new jail construction contradicts their own statement that “more jail does not equal greater public safety.”40 Mass incarceration cannot be solved through the construction of new jails, because mass incarceration as a phenomenon has been perpetrated through the widespread construction of new jails and prisons throughout the United States since the 1970s.41

The city’s solution to mass incarceration—building new jails—is not only illogical, it also does not address the root causes that have driven increasing rates of incarceration. The Lippman Commission and the Mayor’s Office of Criminal Justice Reform treat the rate of incarceration as fixed by natural law, not as an outcome of social, legal, policing, and policy decisions—not, in other words, as the socially constructed variable of racial capitalism that it is. Beginning in the 1970s, increasing rates of incarceration in the U.S. were precipitated by the dismantling of the welfare state42 and a brutal backlash against Black liberation movements.43 Originating in slave patrols, indigenous dispossession, and strike suppression,44 police in the 1970s increasingly targeted well-organized and militant communities oppressed by racial capitalism and marginalized by what Ruth Wilson Gilmore terms “organized abandonment”: deindustrialization, the destruction of union jobs, and the slashing of social welfare.45 Policing, especially “broken windows” policing,46 and incarceration came to be seen as solutions to the problems of Black revolutionary organizing and crises of racial capitalism.47 But these policing practices only exacerbated the crises experienced by the urban working class, and have never increased public safety.48 In fact, policing and incarceration have decreased public safety for Black and Brown residents of cities across the United States;49 New York City is no exception.50

The Lippman Commission purports to understand that “a big part of the problem is the model that Rikers Island embodies.”51 But jails themselves are the models which need critiquing, as isolation, banishment, and confinement are intrinsically violent and inhumane.52 Countless organizations, including the ACLU,53 the NAACP,54 and the United Nations55 have brought attention to the human rights abuses involved in the involuntary confinement of humans in jails, prisons, and particularly in conditions of solitary confinement.

NYC cannot simply incarcerate poor people of color and other oppressed people in the hopes that they will somehow go away, part of a larger gentrification process which allows for “safe” investment by developers.56 There is nothing humane about caging human beings rounded up by aggressive and racist policing in so-called state-of-the-art jails. There is nothing humane about designing cages to have a “welcoming face” for the neighborhoods in which they’re built.57 The social crises of homelessness, racialized poverty, and lack of healthcare cannot be solved with incarceration, but instead with investment in housing, employment opportunities, education, and healthcare.

II. Failed Jail Reform Is as Old as the Jails Themselves

Although over the past six years, the jails on Rikers Island have come to represent the violence, dehumanization, and horrors of incarceration in city jails, Rikers hasn’t always been so infamous. In fact, the Rikers Island Penitentiary was first proposed at the turn of the twentieth century to solve the intolerable conditions, violence, overcrowding, and lack of services in existing city jails, most notably in the workhouses on Welfare, Wards, and Randall’s Islands.58 The NYC Department of Corrections and Mayor Walker asserted that Rikers would be “the most modern penal system in the United States,” with humane, sanitary conditions, an emphasis on rehabilitation, “prison keepers” trained in the modern and dignified treatment of incarcerated people, and expanded access to medical, psychiatric, vocational, social, and re-entry services.59 In brief, Rikers in the mid-twentieth century represented not violence and degradation but the best that modern, humane, rehabilitative jailing had to offer.60

In late 1936, as the Rikers Island Penitentiary accepted its first transfer of incarcerated people from the Welfare Island Workhouse, attention turned to conditions of confinement in other city jails, notably the Tombs in Manhattan and the Raymond Street Jail in Brooklyn.61 Although Rikers already wasn’t living up to its promise,62 NYC continued to hold it out as a success story of the modernization of incarceration.63 Through the 1950s and 1960s, when particularly horrifying conditions in the Tombs, the Raymond Street Jail, and the House of Detention for Women came to light, the NYC DOC responded by demolishing existing facilities and building new jails, like the Brooklyn House of Detention, or expanding facilities on Rikers, all in the name of modernizing and humanizing incarceration and easing overcrowding.64

In the early 1970s, months of uprisings in city jails (including the Tombs, the Women’s Detention Center, the Brooklyn and Queens Houses of Detention, and Rikers), coupled with several highly-publicized cases of incarcerated people dying while in detention (due to negligence and suicide), again drew attention to dehumanizing, unsafe, and degrading conditions in the city jails that had been proclaimed mere years before to be “modern,” “clean,” full of sunlight, and geared towards re-entry and rehabilitation.65 Although conditions on Rikers and the Brooklyn and Queens Houses of Detention were no better, the city administration narrowly focused its attention on conditions at the Tombs and responded to this now perpetual and predictable crisis of incarceration by transferring incarcerated people to Rikers.66

In 1974, a federal district court ruled that the city, having been unable to improve conditions in the Tombs, had to either immediately remedy them or shut down the complex entirely.67 The city chose to shut down and rebuild.68 When the Tombs re-opened in 1983, its warden, Thomas Barry, proclaimed: “It’s now a state-of-the-art jail, the most modern jail in the city of New York.”69 Just like today, as Mayor de Blasio extols the modern virtues of his new jails by hailing their allegedly non-penal architectural features, the New York Times noted in 1983 that cells in the new Tombs facility were “painted in bright colors,”70 as though coats of paint could stand in for human dignity. By the late 1980s and early 1990s, the new Tombs were already plagued with scandals.71 History repeated itself with the Rose M. Singer Center (“Rosie’s”) on Rikers, which was erected in 1988 to replace the Correctional Institution for Women on Rikers (re-christened the George Motchan Detention Center when Rosie’s opened, and used as a men’s jail until 2018).72 Rosie’s was extolled as a state-of-the-art jail for women with a “modern 25-bed nursery and job training programs in horticulture, sewing, and culinary arts,”73 and is now widely recognized to expose women to sexual violence74 and death 75 at the hands of correctional officers and indifferent medical providers.

In the 1930s, in the 1950s, in the 1970s, the 1980s, and today, each time the city proposes a new jail construction plan, it does so under the banner of modernization and humanization.76 This rhetoric of progress casts jails which were held up mere decades earlier as perfect examples of rehabilitative and humane penology as currently backward and pre-modern symbols of violence and degradation. Lofty rhetoric aside, NYC couldn’t make a humane and rehabilitative cage in 1930, in 1950, in 1960, in 1970, or in 1980, and every effort to reform incarceration in our city has revealed itself as an extension and perpetuation of its violence. This is the history of jail reform to which the Lippman Commission and the de Blasio Administration have to respond but which they have studiously ignored, banking on the fact that New Yorkers don’t know our shared history of failed jail reform.

III. Trans Liberation and Prison Abolition

Approximately one in six trans people in the United States, and one in two Black trans people, has been incarcerated.77 This is part of a larger structure of transphobia, in which trans people are discriminated against in education,78 employment,79 and housing,80 forced out of homes and communities, and criminalized for surviving—whether due to their alleged or real participation in illicit economies like drugs and sex work, or for self-defense when fighting off transphobic attackers. The hyper-policing and criminalization of TGNC people disproportionately impacts low-income TGNC people of color.81 Once incarcerated, TGNC people face extreme sexual, physical, and emotional violence, including being denied the right to gender self-determination and being incarcerated in single-gender facilities misaligned with their true genders.82 The criminalization and incarceration of trans women of color also leads to their death at the hands of the state.83

Rikers is no exception. On Friday, June 7, 2019, Layleen Cubilette Polanco, an Afro-Latina trans woman, was found dead in a cell at the Rose M. Singer Center on Rikers Island.84 Ms. Polanco was twenty-seven years old and a member of the House of Xtravaganza.85 The criminalization of Ms. Polanco, who deserved care instead of punishment, has showcased the particularly deadly impact that the criminal legal system has on TGNC people. In August of 2017, Ms. Polanco was targeted by a New York Police Department sting operation and arrested for misdemeanor prostitution86 and the lowest-level drug possession offense.87 She was issued a desk appearance ticket (“DAT”)88 and ushered through a “diversion” court for sex work (“Human Trafficking Intervention Court”).89 By March 2019, Ms. Polanco had missed some allegedly “supportive” services appointments, after which warrants were issued for her arrest.90 When she was re-arrested, the judge likely used the fact of her open warrants and missed court appearances to set bail. Even though Ms. Polanco was ordered released on the new 2019 assault charges, she was held on $500 bail91—newly-set on the 2017 cases—in the Transgender Housing Unit in the Rose M. Singer Center on Rikers for two months.92 By June 2019, she had been taken to a “restrictive housing unit (“RHU”),” otherwise known as solitary confinement, after allegedly participating in a fight.93 She was placed in the RHU even though DOC officials knew that she had a seizure disorder and that solitary confinement is known to exacerbate physical and mental distress.94 On June 7, Ms. Polanco was found dead in a cell.95 Trans women of color like Ms. Polanco are criminalized for surviving at the intersection of racism and transphobia. They are criminalized for defending themselves against violence in communities, as well as for defending themselves against state violence.96

Instead of being targeted for arrest for being a trans woman surviving in a criminalized profession and then court-mandated to use paternalistic and questionably therapeutic services, Ms. Polanco deserved the social, material, and emotional support to live a life free of racism, transphobia, homelessness, and poverty. Court-mandated therapy for sex workers doesn’t end employment or housing discrimination against trans women.97 Supposedly progressive reforms like diversion courts operate through the same individualizing and criminalizing logic as criminal courts, treating people who are struggling to survive as problems to be disciplined, not humans to be uplifted. And when people struggle to meet court expectations or resist their infantilizing and invasive authority, the jails are always there to capture those who “fail” at diversion.98 Once incarcerated, Ms. Polanco was subjected to the notoriously brutal conditions of Rikers and further punished with solitary confinement. The Transgender Housing Unit, meant to keep trans women safe while incarcerated, has never succeeded at this mission.

It is for these reasons that trans liberation and prison-industrial complex abolition are inextricably linked. Because trans women of color live at the intersections of multiple forms of oppression and are brutalized, criminalized, and murdered for merely existing, prison abolition has become a central demand of many within the trans liberation movement. Trans liberation legal theorists have shown how so-called “better” gender-segregation mechanisms (i.e., sorting mechanisms to ensure that trans people are caged with the “correct” gender) or more “gender-responsive” cages99 have not ameliorated the transphobia and violence that incarcerated TGNC people are forced to survive.100 Gender segregation in carceral institutions subjects trans, nonbinary, gender nonconforming, and intersex people to the violence of the gender binary, which does not allow for complexity or self-determination within incarcerated people’s experiences of gender.

Even though the current NYC Board of Correction directives for the caging of trans and intersex people in city jails specify that the DOC “shall not assign a transgender or intersex inmate [sic] to a men’s or women’s facility based solely on the inmate’s [sic] external genital anatomy and that the transgender [or intersex] inmate’s [sic] own views with respect to his or her own safety shall be given serious consideration,”101 the DOC has failed to comply with this directive, routinely denying trans women access to the Transgender Housing Unit and making incarcerated people undergo humiliating and invasive physical examinations to determine their placement within gender-segregated facilities.102

Thus, even when carceral systems purport to be attuned to the needs of TGNC people, they fail, because Departments of Corrections are fundamentally uninterested in the safety or gender-self-determination of incarcerated people. As Ms. Kitty, one of our incarcerated organizers, who has been caged for most of her life in men’s jails and prisons and recently in the Transgender Housing Unit at Rosie’s, writes: “Accountability in the penitentiary is nil. It’s impossible to make jails and prisons safe for trans people. The administration is not interested in the safety of any LGBT people. Protecting us is the last thing on their mind.”103 Or, read the story of R., a Black gender nonconforming person in an upstate prison:

As a whole I’ve endured physical and sexual abuse and to this very day I am targeted being who I am. I do my best to keep my head above water but there are days where I wish the water would eventually swallow me and fill my lungs, but I manage to the best of my ability. I’ve tried to commit suicide multiple times but god wants me to fight for those like myself that are in pain but they aren’t able to advocate for themselves to I have to be strong so I can advocate for them. That’s why I’m still alive. I deal with the bad days better now.104

The unmitigated and unrelenting violence that incarcerated trans and gender nonconforming people face makes the necessity of jail and prison abolition all the more clear and urgent.

IV. Divest to Invest

One of the cornerstones of the No New Jails campaign is our recognition that through investing in community-led social programs, not jails and prisons, we can close Rikers now, reduce interpersonal violence and harm in our communities, and provide people, families, and neighborhoods with the social, cultural, economic, and political resources to thrive and heal from harm, including the structural violence that generations of policing and caging have inflicted on Black and Brown working class New Yorkers. Much of this analysis comes from our currently incarcerated members, who tell us over and over again that jails and prisons don’t work to reduce harm or violence; that we can prevent harm by investing in communities; and that, when harm occurs, transformative justice and accountability outside caging are not only possible, they are necessary. Over the next several pages, you will read letters from some of our currently incarcerated organizers, who describe how they would spend $11 billion to shut down Rikers without building new jails.

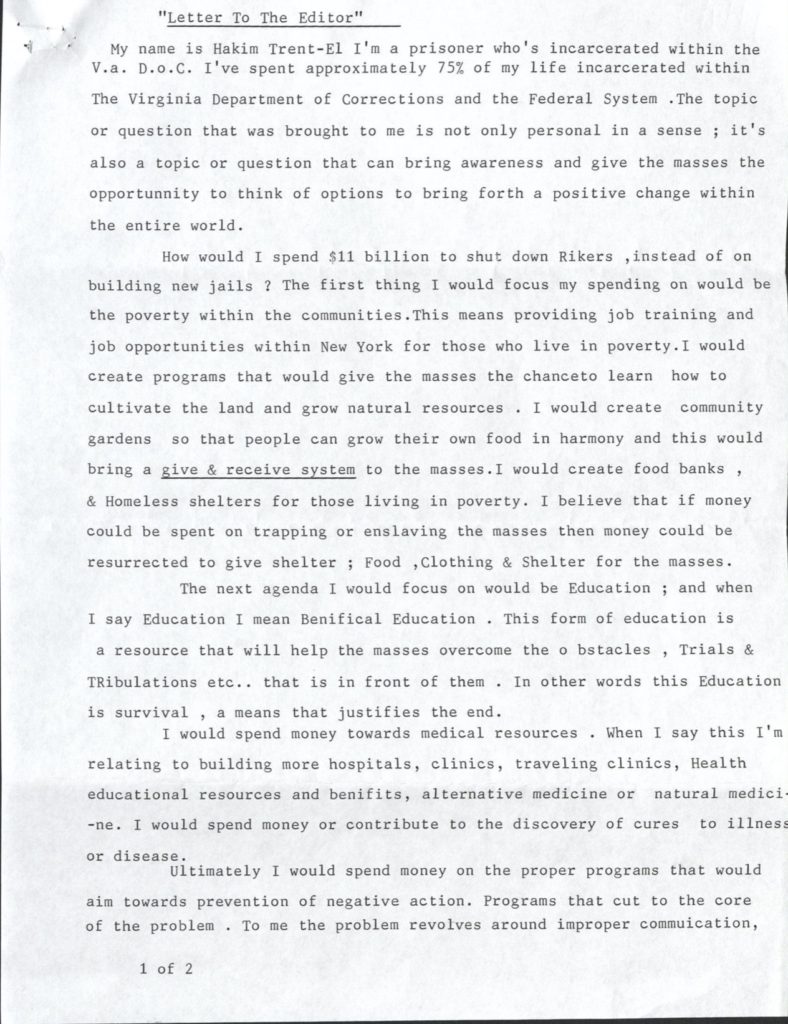

A. Hakim

“Letter to the Editor”: My name is Hakim Trent-El I’m a prisoner who’s incarcerated within the VA. D.o.C. I’ve spent approximately 75% of my life incarcerated within the Virginia Department of Corrections and the Federal System. The topic or question that was brought to me is not only personal in a sense; it’s also a topic or question that can bring awareness and give the masses the opportunity to think of options to bring forth a positive change within the entire world.

How would I spend $11 billion to shut down Rikers, instead of on building new jails? The first thing I would focus my spending on would be the poverty within the communities. This means providing job training and job opportunities within New York for those who live in poverty. I would create programs that would give the masses the chance to learn how to cultivate the land and grow natural resources. I would create community gardens so that people can grow their own food in harmony and this would bring a give & receive system to the masses. I would create food banks & homeless shelters for those living in poverty. I believe that if money could be spent on trapping or enslaving the masses then money could be resurrected to give shelter, food, and clothing for the masses.

The next agenda I would focus on would be education; and when I say education I mean beneficial education. This form of education is a resource that will help the masses overcome the obstacles, trials & tribulations that are in front of them. In order words this education is survival, a means that justifies the end.

I would spend money towards medical resources. When I say this I’m relating to building more hospitals, clinics, traveling clinics, health educational resources and benefits, alternative medicine or natural medicine. I would spend money or contribute to the discovery of cures to illness or disease.

Ultimately I would spend money on the proper programs that would aim towards prevention of negative action. Programs that cut to the core of the problem. To me the problem revolves around improper communication, lack of social skills; lack of parenting or guidance; non-active role models, mental health issues etc. We as a community must address these things head on so that the absence of prisons and jails can be looked upon as an option that will bring success.

The obvious is that the Prison Industrial Complex is “Big Business” for capitalism and this generation is only the future of Chattel Slavery or Perpetual Slavery. A country that thrives off the blood, sweat & tears of the masses. The judicial system means of justice is not prescribed for those of poverty, the minority, so-called colored, etc. The judicial system means of justice is keep the rich getting more richer and the poor more poorer by keeping them at the bottom as workers within the Prison Industrial Complex. The is modern day slavery. We must look into the minds of the slaves; today you will see that the slavery was never abolished. The slave today knows that the Emancipation Proclamation was only a means to legalize what the Prisons & Jails are today. There’s no correction within in a system that aims to destroy the spirit and the soul. A system that places the masses in slavery and calls this correction is a corrupt, hypercritical system that has placed it’s noose around the neck of salvation. How shall integrity face oppression?

The $11 billion inside the hands of the pious with the ambition to refine the community will be the best approach. I envision community centers being built where children can go and learn & play. Where people can actively communicate and learn to love instead of Hate.

Hakim Trent is an advocate for change and the upliftment of fallen humanity.

[signed], 6/14/19 A.D.

Hakim Trent-El

Permission to copy, publish and circulate this writing. Please copy, publish and pass this along to the masses.

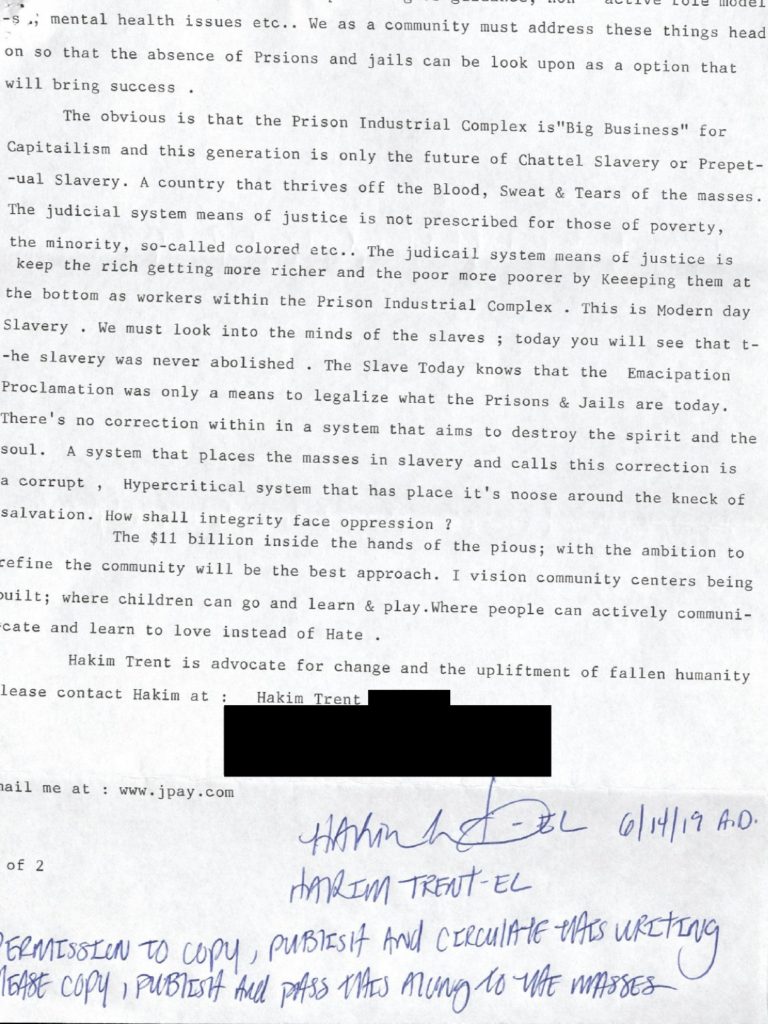

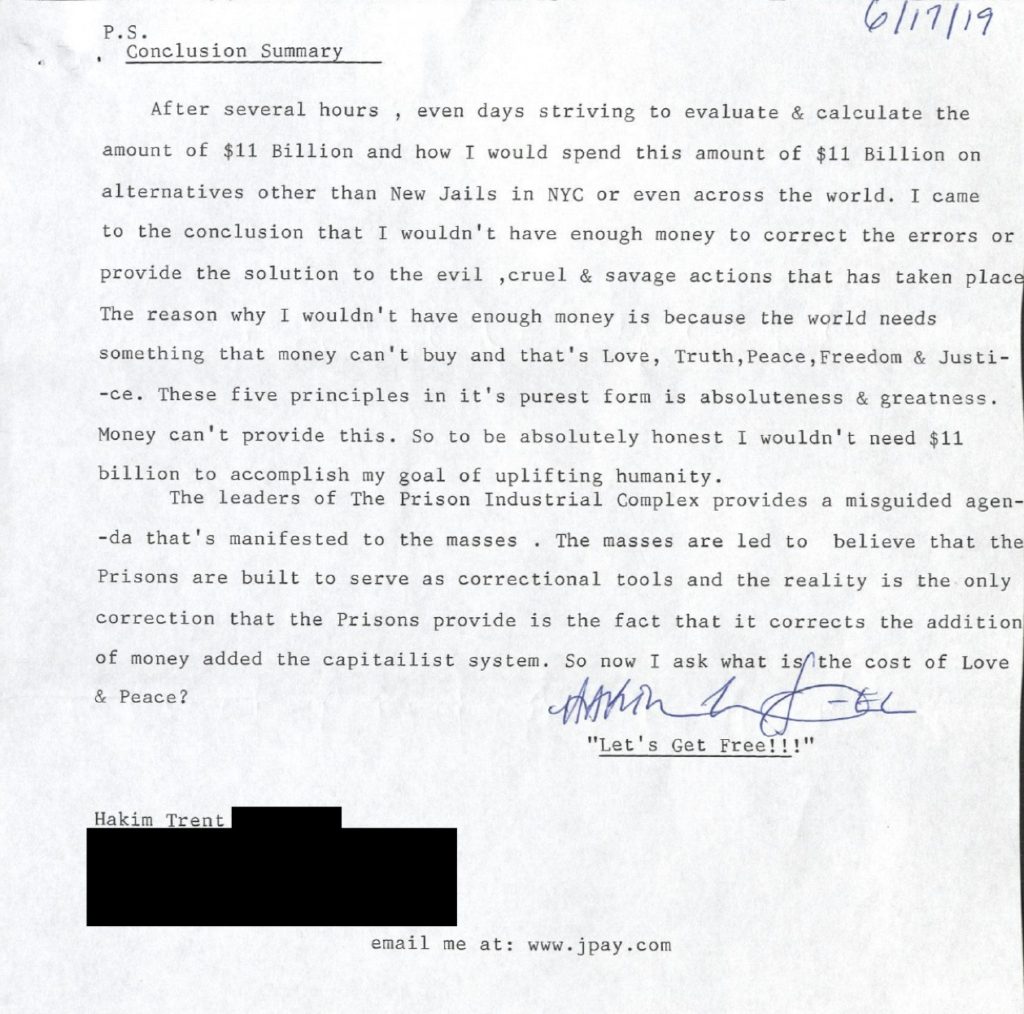

P.S. Conclusion Summary

After several hours, even days striving to evaluate & calculate the amount of $11 Billion and how I would spend this amount of $11 Billion on alternatives other than New Jails in NYC or even across the world, I came to the conclusion that I wouldn’t have enough money to correct the errors or provide the solution to the evil, cruel & savage actions that has taken place. The reason why I wouldn’t have enough money is because the world needs something that money can’t buy and that’s Love, Truth, Peace, Freedom & Justice. These five principles in their’ purest form is absoluteness & greatness. Money can’t provide this. So to be absolutely honest I wouldn’t need $11 billion to accomplish my goal of uplifting humanity.

The leaders of The Prison Industrial Complex provide a misguided agenda that’s manifested to the masses. The masses are led to believe that the Prisons are built to serve as correctional tools and the reality is the only correction that the Prisons provide is the fact that it corrects the addition of money added the capitalist system. So now I ask what is the cost of Love & Peace?

[signed] Hakim Trent-El, “Let’s Get Free!!!”

View the PDF of Hakim’s letter as written here.

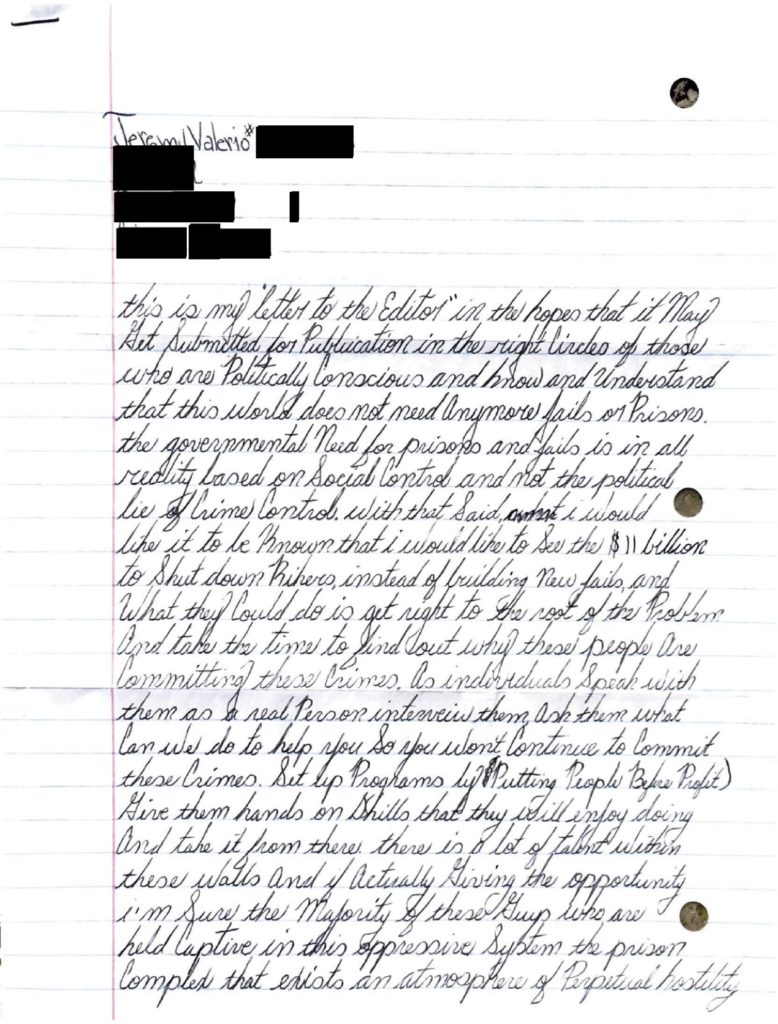

B. Jeremy

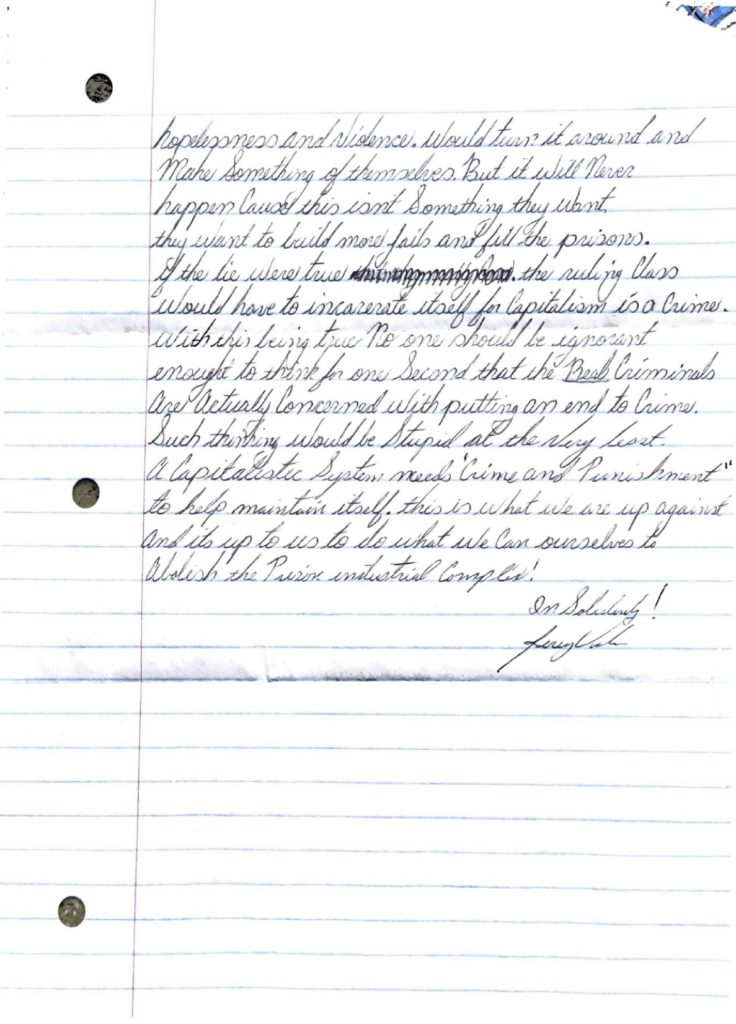

This is my “Letter to the Editor” in the hopes that it may get submitted for Publication in the right Circles of those who are Politically Conscious and know and understand that this world does not need any more jails or prisoners. The governmental need for prisons and jails is in all reality based on Social Control and not the political lie of crime control. With that said, what I would like it to be known that I would like to see the $11 billion to Shut down Rikers, instead of building new jails, and what they could do is get right to the root of the Problem and take the time to find out why these people are committing these crimes. As individuals, Speak with them; as a real Person, interview them. Ask them what can we do to help you So you won’t continue to commit these crimes. Set up Programs by Putting People before Profit, give them hands on skills that they will enjoy doing and take it from there. There is a lot of talent within these walls and if actually given the opportunity I’m sure the majority of these Guys who are held Captive in this oppressive System—the Prison Complex that exists an atmosphere of Perpetual hostility hopelessness and violence would turn it around and make something of themselves. But it will never happen because this isn’t Something they want they want to build more jails and fill the prisons. If the lie were true the ruling class would have to incarcerate itself for capitalism is a crime. With this being true no one should be ignorant enough to think for one second that the Real criminals are actually concerned with putting an end to crime. Such thinking would be stupid at the very least. A capitalistic system needs “Crime and Punishment” to help maintain itself. This is what we are up against and it’s up to us to do what we can ourselves to abolish the Prison Industrial Complex!

In Solidarity!

Jeremy Valerio [signed]

View the PDF of Jeremy’s letter as written here.

C. Lee

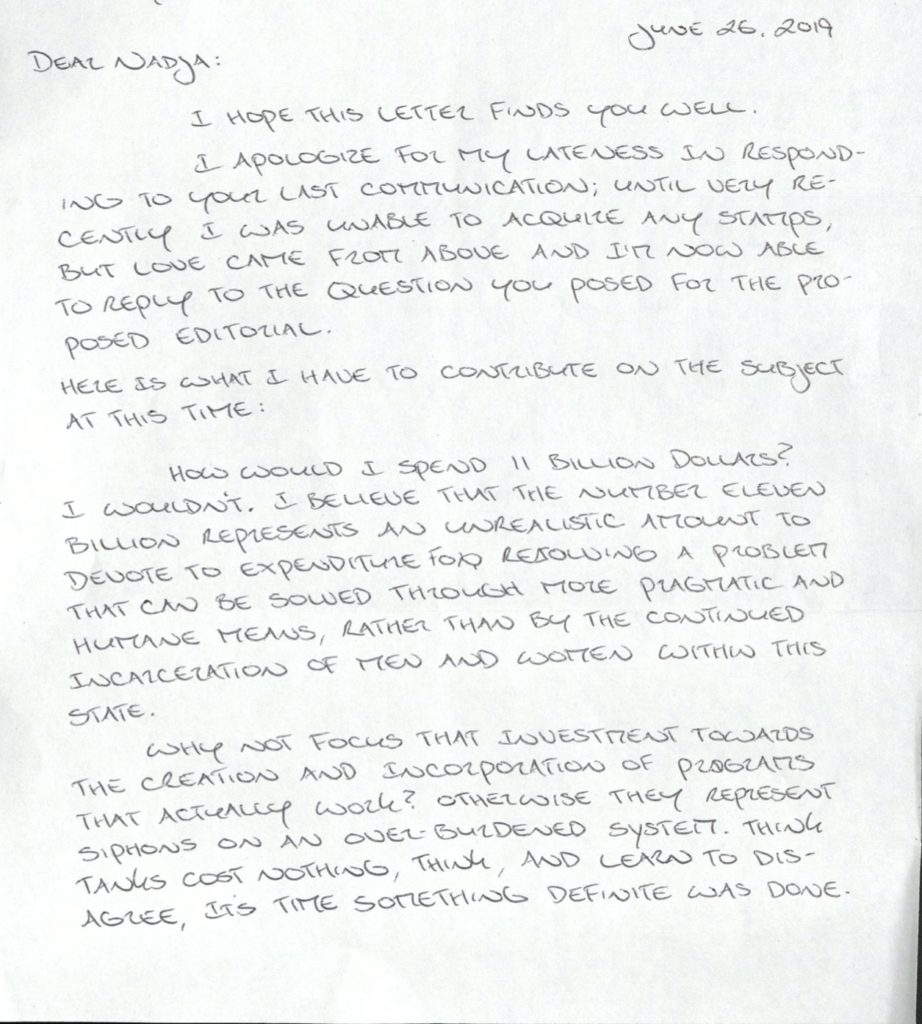

June 26, 2019

Dear Nadja:

I hope this letter finds you well.

I apologize for my lateness in responding to your last communication; until very recently I was unable to acquire any stamps, but love came from above and I’m now able to reply to the question you posed for the proposed editorial.

Here is what I have to contribute on the subject at this time:

How would I spend 11 billion dollars? I wouldn’t. I believe that the number eleven billion represents an unrealistic amount to devote to expenditure for resolving a problem that can be solved through more pragmatic and humane means, rather than by the continued incarceration of men and women within this state.

Why not focus that investment towards the creation and incorporation of programs that actually work? Otherwise they represent siphons on an over-burdened system. Think tanks cost nothing, think, and learn to disagree, it’s time something definite was done.

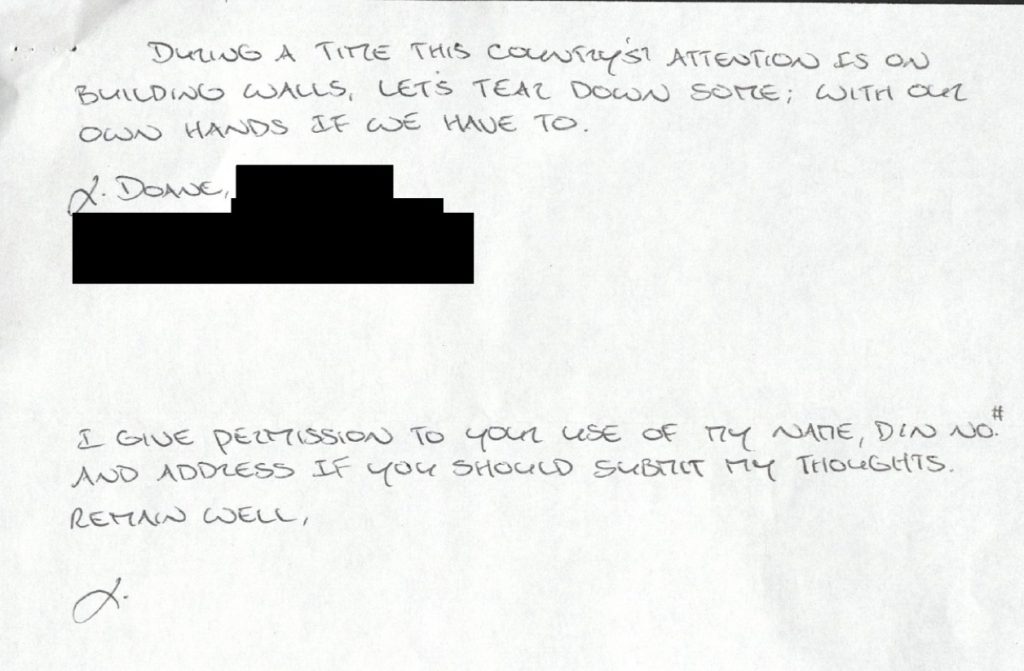

During a time this country’s attention is on building walls, let’s tear down some; with our own hands if we have to.

I give permission to your use of my name, din no.#, and address if you should submit my thoughts.

Remain well,

L.

View the PDF of Lee’s letter as written here.

D. Osha

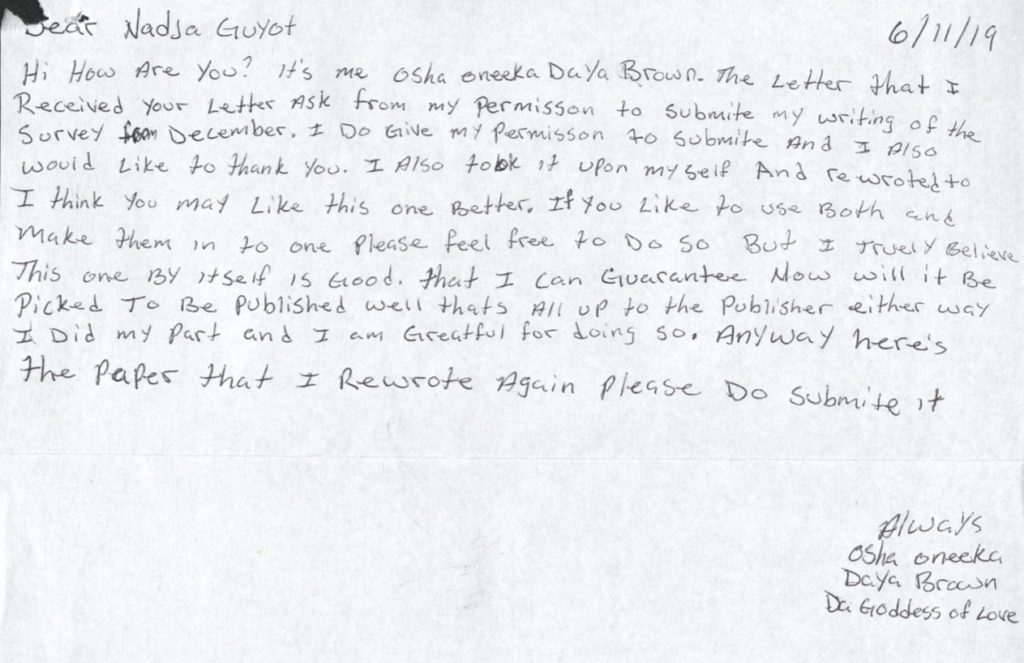

6/11/19

Dear Nadja,

Hi How Are you? It’s me Osha Oneeka Daya Brown. The Letter that I Received your Letter Ask from my permission to submit my writing of the survey from December. I Do Give my Permission to submit And I Also Would Like to thank you. I Also took it upon myself And re-wrote to I think you may Like this one Better. If you Like to use Both and make them into one Please feel free to do so But I Truly Believe This one By itself is Good. that I can Guarantee Now will it Be Picked To Be Published well that’s All up to the Publisher either way I Did my Part and I am Grateful for doing so. Anyway here’s the paper that I Rewrote Again Please Do Submit it.

Always

Osha Oneeka

Daya Brown

Da Goddess of Love

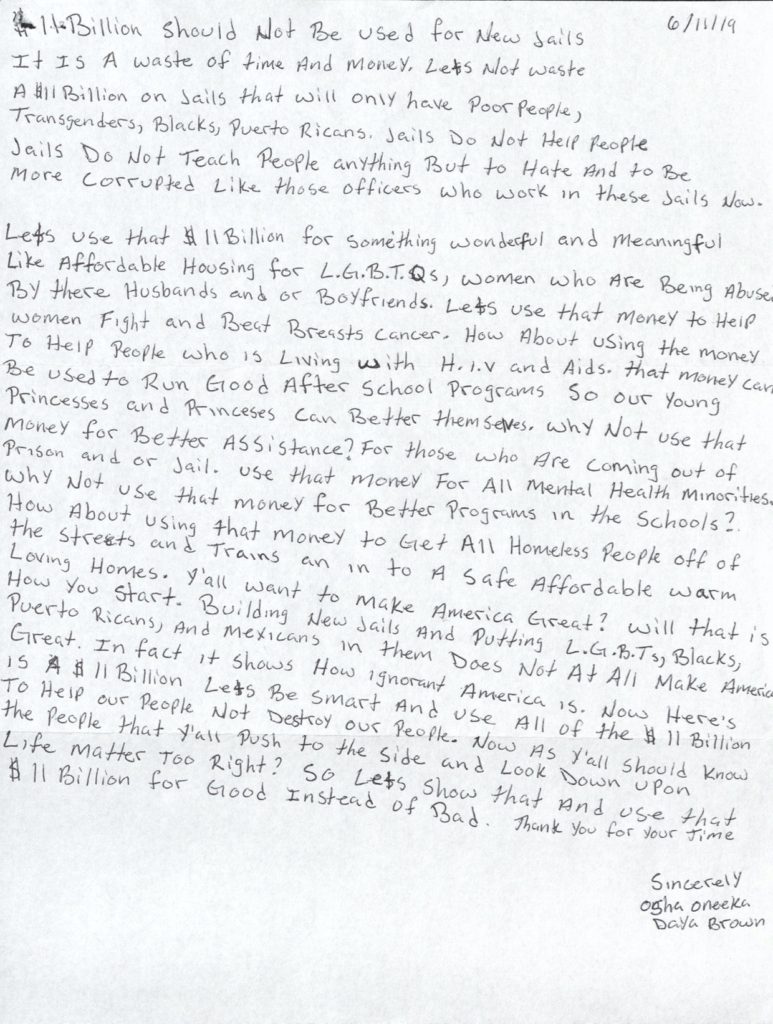

6/11/19

$11 Billion should Not Be used for New Jails.

It Is A waste of time And money. Let’s Not waste

a $11 Billion on Jails that will only have Poor People,

Transgender, Blacks, Puerto Ricans. Jails Do Not Help People

Jails Do Not Teach People anything But to Hate And to Be More Corrupted Like those officers who work in these Jails Now.

Let’s use that $11 Billion for something wonderful and meaningful

Like Affordable Housing for L.G.B.T.Qs, women who are Being Abused By their Husbands and or Boyfriends. Let’s use that money to Help Women Fight and Beat Breast cancer. How about using the money to Help People who are Living with H.I.V and Aids. That money can be used to Run Good After School Programs so our Young Princesses and Princes Can Better themselves. Why Not use that Money for Better Assistance? For those who are coming out of Prison and or Jail. Use that money For All Mental Health Minorities. Why Not use that money for Better Programs in the Schools?

How About using that money to Get All Homeless People off of The streets and trains and into Safe, Affordable, Warm, Loving Homes. Y’all want to make America Great? Well, that is How You Start. Building New Jails and Putting L.G.B.T.s, Blacks, Puerto Ricans, and Mexicans in them Does Not At All Make America Great. In fact, it shows How ignorant America is. Now Here’s To Helping our People, Not Destroying Our People. Now, As Y’all should know: The People that y’all Push to the side and Look Down Upon, Their Life Matters Too, Right? So Let’s show that and use that $11 Billion for Good Instead of Bad. Thank you for your Time.

Sincerely,

Osha Oneeka

Daya Brown

View the PDF of Osha’s letter as written here.

E. Sterling

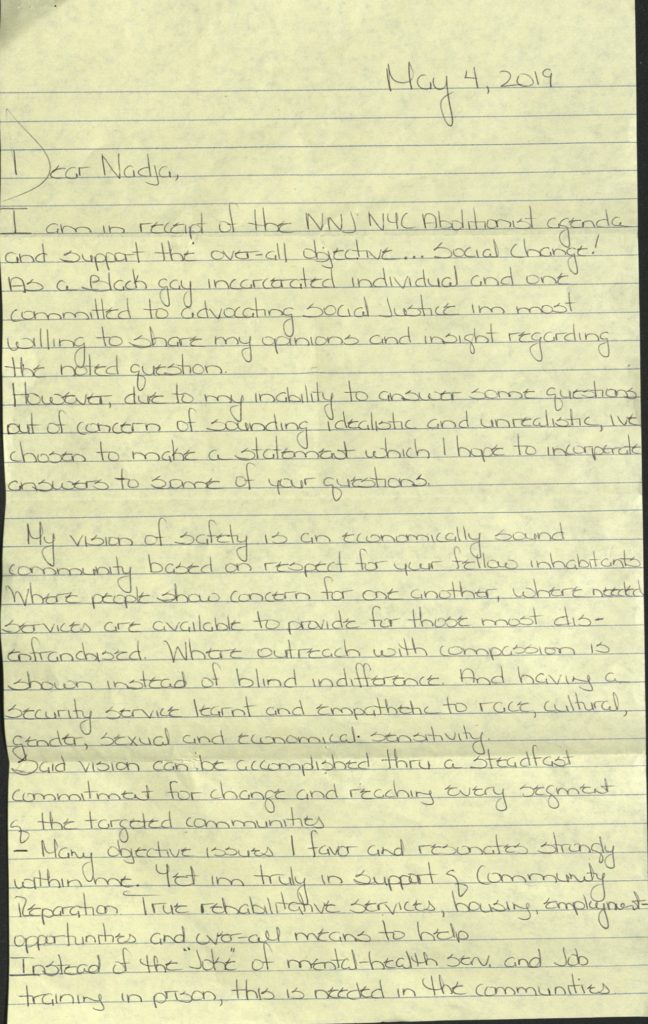

May 4, 2019

Dear Nadja,

I am in receipt of the NNJ NYC Abolitionist agenda and support the overall objective . . . social change! As a Black gay incarcerated individual and one committed to advocating social justice I’m most willing to share my opinions and insight regarding the noted question.

However, due to my inability to answer some questions out of concern of sounding idealistic and unrealistic, I’ve chosen to make a statement which I hope to incorporate some of your questions.

My vision of safer is an economically sound community based on respect for your fellow inhabitants Where people show concern for one another, where needed services are available to provide for those most disenfranchised. Where outreach with compassion is shown instead of blind indifference. And having a security service learnt and empathetic to race, cultural, gender, sexual and economical sensitivity.,

Said vision can be accomplished through a steadfast commitment for change and reaching every segment of the targeted communities

Many objective issues I favor resonates strongly within me. Yet I’m truly in support of community reparations, true rehabilitative services, housing, employment opportunities, and overall means to help, instead of the “joke” mental-health services and job training in prison. This is needed in the communities

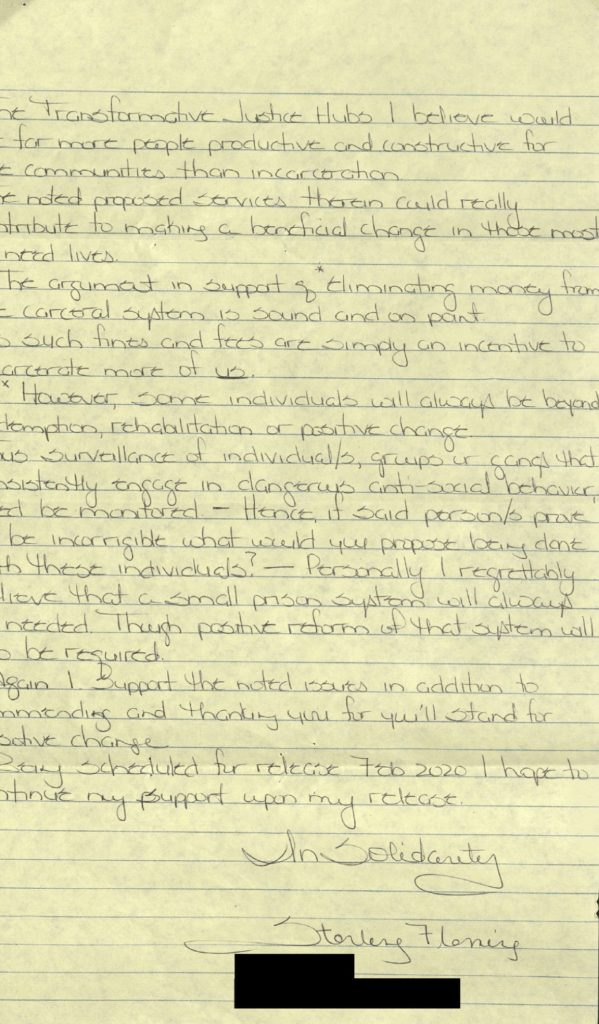

The transformative justice hubs I believe would be for more people productive and constructive for the communities than incarceration.

The noted proposed services therein could really contribute to making a beneficial change in the lives of those most in need.

The argument in support of eliminating money from the carceral system is sound and on point, as such fines and fees are simply an incentive to incarcerate more of us.

However, some individuals will always be beyond redemption, . . . rehabilitation, or positive change.

Thus, surveillance of individual/s, groups or gangs that consistently . . . engage in dangerous anti-social behavior, need to be monitored. Hence, if said persons prove to be incorrigible what would you propose being done with these individuals? Personally I regrettably believe that a small prison system will always be needed. Though positive reform of that system will also be required.

Again I support the noted issues in addition to commending and thanking you for you will stand for positive change.

In Solidarity,

Sterling Fleming

View the PDF of Sterling’s letter as written here.

† No New Jails NYC would like to thank our abolitionist comrades—past, present, and future—who have contributed to our collective strength, political analysis, and power, and have shown us that a world without police, prisons, jails, and borders is possible and necessary for our collective liberation. We would especially like to thank all of you who have struggled alongside us this past year to push for a city without Rikers and without new jails, and to uplift the contributions, leadership, and vision of our incarcerated organizers. It is our duty and honor to fight alongside you all.

Footnotes

- How We Got Here, No New Jails NYC, https://perma.cc/2JNE-SWMN (last visited Dec. 14, 2019).

- About, Critical Resistance, https://perma.cc/P3K8-48LU (last visited Dec. 14, 2019); Our Partners, No New Jails NYC, https://perma.cc/Z2PZ-GQKX (last visited Dec. 14, 2019).

- Million Hoodies Movement for Justice, https://perma.cc/3FZD-736X (last visited Dec. 14, 2019).

- About, Black Lives Matter, https://perma.cc/325P-PM5N (last visited Dec. 14, 2019).

- Carlos Allicea et al., Community in Unity: Fighting Prison Construction in the South Bronx, Left Turn (Feb. 1, 2007), https://perma.cc/T3BB-Q75H

- No New Jails NYC, supra note 2; Safety Beyond Policing, https://perma.cc/5PWX-C7CB (last visited Dec. 14, 2019).

- No New Jails NYC, supra note 2; About Us, Take Back the Bronx, https://perma.cc/3XL8-SHHG (last visited Dec. 14, 2019).

- About BYP100, Black Youth Project 100, https://perma.cc/7W5A-8U6E (last visited Dec. 14, 2019); No New Jails NYC, supra note 2.

- About ALP, Audre Lorde Project, https://perma.cc/5CC9-LZRQ (last visited Mar. 18, 2020).

- SRLP’s Prison Organizing and Advocacy, Sylvia Rivera Law Project, https://perma.cc/U8CN-HFJF (last visited Mar. 18, 2020).

- About, Incarcerated Workers Organizing Committee, https://incarceratedworkers.org/about (last visited Mar. 18, 2020).

- Our Story, Black & Pink, https://perma.cc/MN45-UQDK (last visited Mar. 18, 2020).

- City Council Approves Controversial Plan to Replace Rikers with Borough-Based Jails, CBS N.Y. (Oct. 17, 2019, 11:59 PM), https://perma.cc/P8VU-JZTS.

- Matthew Haag, 4 Jails in 5 Boroughs: The $8.7 Billion Puzzle over How to Close Rikers, N.Y. Times (Sept. 4, 2019), https://perma.cc/86LJ-A5XN; see NYC Mayor’s Office of Criminal Justice, Smaller, Safer, Fairer: A Roadmap to Closing Rikers Island 30 (2018), https://perma.cc/6CJJ-ZQLJ. The proposed Queens jail will include a maternity ward and nursery. See Mark Hallum, Office of Criminal Justice Reveals Early Schematics of Kew Gardens Jail Proposal, QNS (Apr. 24, 2019, 3:30 PM), https://perma.cc/8YGJ-W3BE.

- See Memorandum from NYC Health + Hosps./Corr. Health Servs. (Mar. 8, 2019), https://perma.cc/CGM5-UF4S.

- The City Council vote on October 17, 2019 was the culmination of a Uniform Land Use Review Procedure (ULURP) authorizing the construction of four new jails in NYC at the selected locations in the Bronx, Brooklyn, Manhattan, and Queens. Closing the current facilities on Rikers Island was not the subject of the vote. See Anna Sanders, De Blasio Says Real Estate Development on Rikers Island ‘Not on the Table’ After Closure in 2026, N.Y. Daily News (June 21, 2019, 12:12 PM), https://perma.cc/NP9H-LU4G (“De Blasio stressed he’d be out of office by the time a final decision on the future of Rikers was made and the process could play out over the next 10 to 15 years.”).

- Local jails like the facilities on Rikers Island are under the jurisdiction of New York State, rather than local city or county officials, and thus any land use proceeding to restrict land use on Rikers Island passed by the City Council will ultimately be subject to New York State authority. See, e.g., County of Cayuga v. McHugh, 4 N.Y.2d 609, 614 (1958) (holding that Cayuga County, as a “political subdivision[] of the State, created by the State Legislature and possessing no power save that deputed to [it] by that body,” had no power to challenge a decision of the State Commission of Correction requiring the county to close the jail) (citing N.Y. Correct. Law § 45 (McKinney 2019), which grants the Commission vast authority over local jails); see also N.Y. State Comm’n of Corr. v. Ruffo, 550 N.Y.S.2d 746, 748 (App. Div. 1990) (“[T]he State Legislature has the power to limit the rights granted to counties vis-a-vis county jails and that these can be limited, curtailed and abolished.”). For a more detailed discussion of why a City Council land use proceeding will not result in the closing of the facilities on Rikers Island, see No New Jails NYC, Free the People, Free the Land, Medium (Oct. 15, 2019), https://perma.cc/XJK3-UV8Y (discussing the likelihood of extensive litigation to enforce the City Council’s land use amendment and similar lengthy litigation around the closure of the Manhattan Detention Complex, known as the “Tombs,” from 1970 to 1974).

- See, e.g., Press Release, N.Y.C. Council, Speaker Corey Johnson and Mayor Bill de Blasio Agreement to Ban Incarceration on Rikers Island Passes Council’s Land Use Committee (Oct. 10, 2019), https://perma.cc/7Q6H-AVS5 (quoting Mayor de Blasio as saying that “[w]e’re making our commitment ironclad and ensuring no future administration can reverse all the progress we’ve made.”).

- See, e.g., Indep. Comm’n on N.Y.C. Criminal Justice and Incarceration Reform, A More Just New York City (2017), https://perma.cc/4L6C-NSRP; The Plan, City of N.Y., https://perma.cc/V923-KJGD (last visited Dec. 20, 2019).

- See, e.g., Rosa Goldensohn, Jail Doctors Made Man Impotent by Failing to Treat 6-Day Erection: Lawsuit, DNAinfo (June 8, 2015, 7:17 AM), https://perma.cc/3GTL-W634; Shayna Jacobs, Correction Officer Accused of Dealing Contraband to Inmates in Manhattan Jail Busted on Drug Charges, N.Y. Daily News (May 11, 2015, 7:43 PM), https://perma.cc/4QD6-HJXY; John Surico, The Legacy of Violence at the Manhattan Jail Known as the ‘Tombs,’ Vice (July 29, 2015, 1:05 AM), https://perma.cc/C5AD-A22R (discussing the violent history of reported abuse at the Manhattan Detention Complex, known as the “Tombs”).

- The new Manhattan and Brooklyn jails are to be built on the current locations of the Manhattan Detention Complex (the “Tombs”) and the Brooklyn House of Detention, which must be closed down and destroyed before the new jails can be built. As both of these jails currently house incarcerated people, those people must be moved to jails on Rikers Island while the new jails are built. See No New Jails NYC, We Will Move All of Them to Rikers Island, YouTube (July 27, 2019), https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=FWOd-H9SRqU (quoting NYC Department of Corrections Commissioner Cynthia Brann as saying that “[w]e would move all of the inmates [sic] to Rikers Island in available beds.”).

- Transgender and gender nonconforming are umbrella terms to describe individuals whose gender identity differs from the sex they were assigned at birth. See Fact Sheet: Transgender & Gender Nonconforming Youth in School, Sylvia Rivera Law Project, https://perma.cc/9LG2-T9EE (last visited Dec. 14, 2019).

- Maurice Chammah, Inside the Battle to Close Rikers, Marshall Project (Mar. 22, 2019, 10:00 AM), https://perma.cc/SM4U-4FLE.

- City of N.Y., supra note 19.

- N.Y.C. Dep’t of Corr., NYC Department of Corrections at a Glance (2019), https://perma.cc/775H-MT7N; N.Y. State Dep’t of Health, Medicaid Redesign 1115 Demonstration Amendment Application: Continuity of Coverage for Injustice-Involved Populations 3 (2019), https://perma.cc/J8PX-E7VT.

- See Editorial Board, A Big Victory for Public Defense in New York, N.Y. Times (June 24, 2016), https://perma.cc/MWB6-ZKXW; see also Lauren-Brooke Eisen, Paying for Your Time: How Charging Inmates Fees Behind Bars May Violate the Excessive Fines Clause, 15 Loy. J. Pub. Int. L. 319, 328 n.57 (2014).

- Caroline Wolf Harlow, U.S. Dep’t of Justice, Education and Correctional Populations 3 tbl.2 (2003), https://perma.cc/RF6Z-XGYJ.

- See L.A. Cty. Sheriff’s Dep’t, Custody Division Year End Review 25 (2016), https://perma.cc/2BVK-RLDE; State of Ill. Circuit Court of Cook Cty., Bail Reform in Cook County 24-30 (2019), https://perma.cc/6JTP-39HK; Policy Statement, Chi. Appleseed & the Chi. Council of Lawyers, The Data Is Out: Bond Reform in Cook County Has Been a Tremendous Success (June 11, 2019), https://perma.cc/UBV2-A7VY.

- Vera Inst. of Justice, Empire State of Incarceration, https://perma.cc/AH8X-CHMZ (last visited Feb. 9, 2020).

- See Jeff Thaler, Punishing the Innocent: The Need for Due Process and the Presumption of Innocence Prior to Trial, 1978 Wis. L. Rev. 441 (1978) (discussing pretrial detention as a punitive measure that sidesteps due process and imposes, in effect, a presumption of guilt on those awaiting trial).

- Approximately fifty percent of felony charges in NYC will eventually be dismissed (thirty percent dismissed outright; twenty percent dismissed as adjournments in contemplation of dismissal), and another twenty to thirty percent will be pleaded down to misdemeanors. Of the cases actually charged as felonies, ninety-six percent are resolved through plea deals. But, if a person goes to trial on a felony in NYC, they have a fifty percent chance of being found not guilty. This is clear and persistent evidence of over-policing and a concomitant lack of concern for survivors of serious interpersonal harm, who get very little (if any) resolution or healing from the criminal legal system. For a county-by-county breakdown of arrest dispositions in New York, see 2014 – 2018 Dispositions of Adult Arrests, N.Y. State Div. of Criminal Justice Servs., https://perma.cc/9U6B-F3KT (last visited Dec. 19, 2019).

- See generally Ralph A. Weisheit & John M. Klofas, The Impact of Jail: Collateral Costs and Affective Response, 14 J. Offender Rehabilitation 51 (1990).

- See Paul Heaton et al., The Downstream Consequences of Misdemeanor Pretrial Detention, 69 Stan. L. Rev. 711, 717-18 (2017).

- Jennifer Gonnerman, Before the Law, New Yorker (Sept. 29, 2014), https://perma.cc/WL6D-ES28

- Martin F. Horn, Fixing the Jail Where Kalief Browder Was Held, Marshall Project (June 9, 2015, 12:10 PM), https://perma.cc/FP5K-YZ2M.

- See Hope Reese, The Case for Shutting Down New York City’s Rikers Island Jail, Vox (June 7, 2018, 12:20 PM), https://perma.cc/XA7Q-FJ7N; Christina Sterbenz & Sarah Jacobs, This Man Is Growing a Movement to Shut Down One of the Country’s Most Notorious Jails, Bus. Insider (Aug. 13, 2016, 8:01 AM), https://perma.cc/M75C-EJMN.

- J. David Goodman, De Blasio Says Idea of Closing Rikers Jail Complex is Unrealistic, N.Y. Times (Feb. 16, 2016), https://perma.cc/K9EV-FXZH.

- See Indep. Comm’n on N.Y.C. Criminal Justice and Incarceration Reform, supra note 19.

- Id. at 28.

- Id. at 14.

- See Peter Wagner, Prison Policy Initiative, Tracking State Prison Growth in 50 States (2014), https://perma.cc/CLE3-XZ7H; see generally Bernard E. Harcourt, Neoliberal Penality, 14 Theoretical Criminology 74 (2010).

- State economic policy of the last half-century has resulted in the spread of a generalized condition of poverty and indebtedness in the United States, as well as the growth of racial wealth disparity through organized abandonment. “Crimes of survival,” such as petit larceny or fare beating, exist in a larger context of violence against poor people of color, particularly Black and Latinx people, in which police and prisons play a huge part. See, e.g., Jordan T. Camp, Incarcerating the Crisis: Freedom Struggles and the Rise of the Neoliberal State passim (2016); Judah Schept, Progressive Punishment: Job Loss, Jail Growth, and the Neoliberal Logic of Carceral Expansion passim (2015).

- Camp, supra note 42, at 8-9; Schept, supra note 42, at 55.

- See, e.g., Alex Vitale, The Myth of Liberal Policing, New Inquiry (Apr. 5, 2017), https://thenewinquiry.com/the-myth-of-liberal-policing/; Kristian Williams, The Demand for Order and the Birth of Modern Policing, History Is a Weapon, Dec. 2003, https://perma.cc/9Y4X-T5XF; Gary Potter, The History of Policing in the United States, Part 3, E. Ky. U.: Police Stud. Online (July 9, 2013), https://perma.cc/Q97U-VWSW.

- See Ruth Wilson Gilmore & Craig Gilmore, Beyond Bratton, in Policing the Planet: Why the Policing Crisis Led to Black Lives Matter 173, 187 (Jordan T. Camp & Christina Heatherton eds., 2016).

- James Q. Wilson & George L. Kelling, Broken Windows, Atlantic Monthly, Mar. 1992, at 29. “Broken windows” policing, introduced to the streets of New York by criminologists Wilson and Kelling and deployed by former New York City Mayor Rudolph Giuliani and Police Commissioner Bill Bratton, focuses on policing environments which are “broken” or abandoned, with the theory that they beget criminal activity. Kelling and Wilson asserted that “disorder and crime are usually inextricably linked,” id. at 31, in their thinly veiled racist analysis of urban disorder and crime, emblematic of criminology at the time.

- See e.g., Michelle Alexander, The New Jim Crow: Mass Incarceration in the Age of Colorblindness 40-58 (2010); Sandra Bass, Policing Space, Policing Race: Social Control Imperatives and Police Discretionary Decisions, 28 Social Justice 156 (2001), https://perma.cc/X7BZ-DSNG; Sam Mitrani, Stop Kidding Yourself: The Police Were Created to Control Working Class and Poor People, LaborOnline (Dec. 29, 2014), https://perma.cc/82GT-WEKC.

- See Christopher M. Sullivan & Zachary P. O’Keeffe, Letter, Evidence That Curtailing Proactive Policing Can Reduce Major Crime, 1 Nature Hum. Behav. 730 (2017) (finding that, in New York City, aggressive policing of low-level violations is positively related to increased reports of major crime); see generally Camp, supra note 42.

- See Sullivan & O’Keeffe, supra note 48; Camp, supra note 42.

- See e.g., Amanda Geller et al., Aggressive Policing and the Mental Health of Young Urban Men, 104 Am. J. Pub. Health 2321, 2323-24 (2014); Sarah Lustbader, What’s Not to Love About the NYPD Slowdown?, Appeal (Sept. 3, 2019), https://perma.cc/Q847-GPQ2.

- Indep. Comm’n on N.Y.C. Criminal Justice and Incarceration Reform, supra note 19, at 26.

- Don Stemen, Vera Inst. of Justice, The Prison Paradox: More Incarceration Will Not Make Us Safer (2017), https://perma.cc/5ATN-3WJD.

- ACLU, Abuse of the Human Rights of Prisoners in the United States: Solitary Confinement (2011), https://perma.cc/F5E2-KNAR.

- Criminal Justice Fact Sheet, NAACP, https://perma.cc/Q5JW-9G3M (last visited Nov. 5, 2019).

- G.A. Res. 45/111, Basic Principles for the Treatment of Prisoners (Dec. 14, 1990), https://perma.cc/6LSY-24KN.

- See Stephanie Leguichard, Gentrification: Undercover Agent of Mass Incarceration, Marcus Harris Found. (July 23, 2019), https://perma.cc/9TZN-ESXE; Abdallah Fayyad, The Criminalization of Gentrifying Neighborhoods, Atlantic (Dec. 20, 2017), https://perma.cc/3KXA-NQWQ; Casey Kellogg, There Goes the Neighborhood: Exposing the Relationship Between Gentrification and Incarceration, 3 Themis 178, 180 (2015).

- Indep. Comm’n on N.Y.C. Criminal Justice and Incarceration Reform, supra note 19, at 76.

- Letter from Dep’t of Corr. Comm’r Wallis to Taylor Phillips, Chairman of the Comm. of Departmental Org. (Oct. 5, 1926) (on file with author).

- 28 Prison Keepers Graduated at School, N.Y. Times, Mar. 6, 1928, at 19, https://perma.cc/GT49-PP6H; Letter from Dep’t of Corr. Comm’r Wallis to Mayor Walker (Jan. 11, 1927) (on file with author); Letter from the Crime Clinic Committee to Dep’t of Corr. Comm’r Patterson (June 29, 1929) (on file with author).

- Patterson Offers Riker’s Prison Plan, N.Y. Times, June 26, 1928, at 14, https://perma.cc/B9PD-M3XS.

- The city administration’s inability to see (or admit) that intolerable conditions of confinement were widespread and not exclusive to the workhouses is similar to today, where Mayor de Blasio focuses exclusive attention on Rikers even as conditions in other city jails are notoriously dangerous, toxic, and inhumane. See, e.g., Noah Goldberg, Use of Force by Staff Has Tripled at Brooklyn Jail Since 2015, Despite Reforms, Brooklyn Daily Eagle (Oct. 30, 2019), https://perma.cc/T48K-FHAA; Rosa Goldensohn & Reuven Blau, Sweltering City Jail Cells Need Air Conditioning, Says Board of Correction, City (July 23, 2019), https://perma.cc/7TDZ-MKU6; Surico, supra note 20.

- Russell Porter, City Prison Head Fights Crowding, N.Y. Times, Dec. 28, 1954, at 18, https://perma.cc/J84H-ECG6.

- See Anakwa Dwamena, Closing Rikers: Competing Visions for the Future of New York City’s Jails, N.Y. Rev. Books (Oct. 4, 2019, 2:44 PM), https://perma.cc/7WUM-WTJR.

- Just as with the Workhouses in the 1930s and Rikers today, the political will to address conditions of confinement lagged decades behind official knowledge of just how horrible those conditions were. Thus, for example, merely two years after it was built, in 1932, the Women’s House of Detention was already labeled inadequate, but it wasn’t until 1965 that the city decided to address these conditions by demolishing the Women’s House and building a new jail for women on Rikers. That jail, which was completed in 1971, was replaced in 1988 with the Rose M. Singer Center. When the Rose M. Singer Center was built, it was extolled as modern and humane. Today, it is recognized as notoriously violent, subjecting incarcerated women to rape and shackling during pregnancy. See, e.g., Lawrence O’Kane, Stark Inspects Women’s Jail, Asks Action to Cut Overloading, N.Y. Times, Apr. 30, 1958, at 26, https://perma.cc/N3Y4-D76X; Russell Porter, Crowding Eased in City’s Prisons, N.Y. Times, June 12, 1960, at 1, 85, https://perma.cc/GE7W-LHLC; Wagner Inspects 3 Prisons in City, N.Y. Times, Dec. 8, 1955, at 39 https://perma.cc/DE9G-7C4S.

- See, e.g., Martin Arnold, Prisoners in Tombs Riot for Second Day, N.Y. Times, Aug. 12, 1970, at 1, 52, https://perma.cc/ZZT6-QQ7E; Martin Arnold, Rockefeller Refers Jails Crisis to City, N.Y. Times, Aug. 13, 1970, at 1, 24, https://perma.cc/YVK7-9US2; John Richard Dunne, Crusader for Prison Reforms, N.Y. Times, Aug. 19, 1970, at 22, https://perma.cc/J4R7-KNJG.

- Toussaint Losier, Against ‘Law and Order’ Lockup: The 1970 NYC Jail Rebellions, 59 Race & Class 3, 9 (2017) (citing Andrew Schaffer, Vera Inst. of Justice, The Problem of Overcrowding in the Detention Institutions of New York City, at iv (1969), https://perma.cc/D78C-34T6).

- Surico, supra note 20.

- Max H. Seigel, Tombs Closing, N.Y. Times, November 16, 1974, at 23, https://perma.cc/S2NE-9SC8.

- Philip Shenon, Tombs to Reopen with a New Look, N.Y. Times, Oct. 17, 1983, at 1, 27, https://perma.cc/3FQB-QATT.

- Id.

- See, e.g., Celestine Bohlen, Judge Accepts Plan to Ease Crowded Jails, N.Y. Times, Apr. 20, 1989, at B1, https://perma.cc/D26E-X3X3; Selwyn Raab, Judge Orders Payments to 7 Inmates Without Beds, N.Y. Times, Apr. 11, 1991, at B8, https://perma.cc/FPH9-DJX8; Selwyn Raab, Report Accuses New York of Faking Jail Data, N.Y. Times, Apr. 3, 1992, at B1, https://perma.cc/D4RD-3CZS.

- See Jarrod Shanahan & Nadja Eisenberg-Guyot, All Jails Fit to Build, Brooklyn Rail (Feb. 2020), https://perma.cc/W6KA-99W4.

- Rose M. Singer Center Opens on Rikers Island, Correction News (1988), https://perma.cc/3S4L-G4VN.

- John H. Tucker, Rape at Rosie’s, N.Y. Mag.: Intelligencer (June 25, 2018), https://perma.cc/WB2U-FAYG.

- See Erika Eichelberger, “You Call This a Medical Emergency?”: Death and Neglect at Rikers Island Women’s Jail, Intercept (May 29, 2015, 2:06 PM), https://perma.cc/T3HY-PLAL; Natasha Lennard, How New York’s Criminal Justice System Killed a Transgender Woman at Rikers Island, Intercept (June 13, 2019, 12:28 PM), https://perma.cc/2YAM-5KB7.

- See Shanahan & Eisenberg-Guyot, supra note 72.

- Transgender Incarcerated People in Crisis, Lambda Legal, https://perma.cc/F59Y-E3LP (last visited Dec. 17, 2019).

- Logan Casey & Elizabeth Mann Levesque, LGBTQ Students Face Discrimination While Education Department Walks Back Oversight, Brookings Inst.: Brown Center Chalkboard (Apr. 18, 2018), https://perma.cc/2NYB-WBX3.

- Employment, Nat’l Ctr. for Transgender Equality, https://perma.cc/XV8J-ZGLN (last visited Dec. 17, 2019).

- Housing & Homelessness, Nat’l Ctr. for Transgender Equality, https://perma.cc/9H3X-Z26U (last visited Dec. 17, 2019).

- Transgender Incarcerated People in Crisis, supra note 77.

- Id.

- See, e.g., Sandra E. Garcia, Independent Autopsy of Transgender Asylum Seeker Who Died in ICE Custody Shows Signs of Abuse, N.Y. Times (Nov. 27, 2018), https://perma.cc/G7CB-ZGJT; Jack Herrera, Why Are Trans Women Dying in ICE Detention?, Pac. Standard (June 4, 2019), https://perma.cc/BZL9-GHM6.

- Amanda Arnold, A Trans Woman Was Found Dead in Her Rikers Cell. Now Her Family Wants Answers., N.Y. Mag.: The Cut (June 11, 2019), https://perma.cc/Q9LY-DZKF.

- Michael Gold & Sean Piccoli, After a Transgender Woman’s Death at Rikers, Calls for Justice and Answers, N.Y. Times (June 11, 2019), https://perma.cc/L6QR-F9XG.

- N.Y. Penal Law § 230.00 (McKinney 2019).

- N.Y. Penal Law § 220.03 (McKinney 2019); see EJ Dickson, How the Tragic Death of Layleen Polanco Exposes Horrors of Criminalizing Sex Work, Rolling Stone (June 13, 2019, 5:23 PM), https://perma.cc/BSE2-J3CJ.

- Matt Tracy, Questions Abound After Trans Woman’s Death at Rikers, Gay City News (June 12, 2019), https://perma.cc/J8X3-L28C.

- Raven Rakia, Trans Woman’s Death in Rikers Is Still a Mystery. But Why Was She There at All?, Appeal (June 12, 2019), https://perma.cc/L6GQ-7W9L.

- Dickson, supra note 87.

- Diana Tourjée, ‘The State Is Her Ultimate Killer’: How a Trans Woman Died at Rikers, Vice (June 12, 2019, 2:53 PM), https://perma.cc/6A37-RXSE.

- In 2014, the New York City Department of Correction (“DOC”) opened the Transgender Housing Unit (“THU”) for trans women only (not trans men or nonbinary people), on Rikers Island, before moving it to the Tombs, the Manhattan jail designated as being for men, in 2015. Press Release, New York City Department of Correction, DOC Opens New Housing Unit for Transgender Women on Rikers Island (Nov. 18, 2014), https://perma.cc/RY32-3EXV; see Aviva Stahl, New York City Jails Still Can’t Keep Trans Prisoners Safe, Village Voice (Dec. 21, 2017), https://perma.cc/8TGP-W5FY. Thereafter, the THU relocated to the Rose M. Singer Center (colloquially known as “Rosie’s”). See Sessi Kuwabara Blanchard, NYC Jail Deprived Trans Women of MAT for Years, Filter Mag. (June 13, 2019), https://perma.cc/5N4Q-PRU4. Prior to the establishment of the THU, the DOC caged gay and trans people in various “gay tanks,” usually mixed-gender gay wings, in New York City jails until 2005, when the City closed the gay and trans housing unit on Rikers Island. See Paul von Zielbauer, New York Set to Close Jail Unit for Gays, N.Y. Times (Dec. 30, 2005), https://www.nytimes.com/2005/12/30/nyregion/new-york-set-to-close-jail-unit-for-gays.html.

- Dickson, supra note 87.

- Emanuella Grinberg, Cause of Death Revealed for Transgender Woman Who Died at Rikers Island, CNN (July 31, 2019, 6:50 PM), https://perma.cc/5D96-LGNR.

- Id.

- See, e.g., Emma Whitford, NYC Transgender Activist Says She Was Criminalized for Defending Herself Against Abuser, Appeal (Feb. 26, 2018), https://perma.cc/B6LK-VHCA.

- Elizabeth F. Schwartz, The Many Faces of Transgender Discrimination, Am. Ass’n for Just.: Trial Mag. (Oct. 2016), https://perma.cc/T2TG-WLAJ.

- See, e.g., Melissa Gira Grant, Inside NY Courts Where Sex Workers Are ‘Painted as Victims and Treated as Criminals,’ Appeal (Sept. 21, 2018), https://perma.cc/X7BS-2DQ8.

- For examples of the proliferation of “gender responsive” incarceration, see, e.g., Barbara Bloom et al., Nat’l Inst. of Corr., Gender-Responsive Strategies, at v (2003) (defining “gender responsiveness” as “creating an environment . . . that reflects an understanding of the realities of women’s lives and addresses the issues of the women”), https://perma.cc/SMY3-M2AF (quoting Stephanie S. Covington & Barbara E. Bloom, Paper presented at the 52nd Annual Meeting of the Am. Soc’y of Criminology, Gendered Justice: Programming for Women in Correctional Settings 11 (Nov. 2000)); N.Y.C. Planning Comm’n, C 190333 PSY, at 44 (2019), https://perma.cc/EW95-CERD (discussing the implementation of “gender responsive” training for correctional officers within the context of the NYC jail construction plan).

- See, e.g., Gabriel Arkles, Regulating Prison Sexual Violence, 7 Ne. U. L.J. 69 (2015); Gabriel Arkles, Safety and Solidarity Across Gender Lines: Rethinking Segregation of Transgender People in Detention, 18 Temp. Pol. & Civ. Rts. L. Rev. 515 (2009); Morgan Bassichis et al., Building an Abolitionist Trans and Queer Movement with Everything We’ve Got, in Captive Genders: Trans Embodiment and the Prison Industrial Complex 15 (Eric A. Stanley & Nat Smith eds., 2011); Dean Spade, The Only Way to End Racialized Gender Violence in Prisons is to End Prisons: A Response to Russell Robinson’s “Masculinity as Prison,” 3 Cal. L. Rev. Circuit 184 (2012).

- N.Y.C. Bd. of Corr., An Assessment of the Transgender Housing Unit 3 (2018), https://perma.cc/5HHA-U2WA (quoting R. of the City of N.Y. tit. 40, § 5-18(d)-(e) (2019)).

- Id.; see Stahl, supra note 92.

- Letter from Ms. Kitty to author (Apr. 2019) (on file with author).

- Letter from R. to author (Dec. 2018) (on file with author).

…my response was just that 11Billion for what? I am absolutely in agreeance w/shutting down rikers for so many reasons…I am a formerly incarcerated woman (still in the process of transitioning) all to familiar w/the many injustices suffered during and from this particular process…one of the reasons I’d briefly like to touch on is if we can address the surrounding issues like misdemeanors /nonviolent crimes we can begin to get to the core of who really needs us, violent offenders, who are more often than not sentenced excessively and limited in the assistance/help they have access to and receive…more importantly the programs that would help them address the trauma and issues that led to incarceration such as mental health services, are not available…the reality is new laws need to be written and passed in hopes of giving people a second chance …eventually they will be released…we want them as healthy as possible when they are!

_cherish johnson_ and @_nycgirl (twitter)

Pingback: If you’re surprised by how the police are acting, you don’t understand US history | Malaika Jabali | Opinion - NEWZIZ